Coffee-houses

Proliferating as they did in Restoration London, coffee-houses were soon imitated elsewhere. Bath certainly had one by 1679, probably at the sign of the Turk's Head in the Marketplace. Under Robert Sheyler this moved c.1694 to new premises at the upper corner of Cheap Street, where it continued under Elizabeth and Robert Sheyler junior until sometime after 1718. By then a second coffee-house - Benjoy's/Bengy's (after its proprietor Benjamin Jellicot) - had arisen at the south end of Terrace Walk, usefully adjacent to the bowling green, but this eventually fell victim to Wood's redevelopment scheme c.1728. In 1720-1 Thomas Sheyler gave a fresh fillip to Bath's fashionable quarter near Gravel Walks, the future Orange Grove, by opening a coffee-house on a strategic corner site at the exit of an intended pedestrian way (Wade's Passage) from Abbey Churchyard. In a short time it was an indispensable institution.

As genteel places to eat and drink, and to catch up on news, coffee-houses met several needs at once, and did so by charging a subscription for their use. This distanced them from public taverns and kept the company reasonably select. Equally it allowed them to provide a congenial milieu, a range of current newspapers and other publications, and free use of writing materials. Licensed to sell alcohol as well as hot drinks and snacks (rolls, Bath buns, soups, savoury jellies, syllabubs), and often indeed run by ex-wine-and-brandy merchants, coffee-houses above all did duty as male clubs. In London particular interest groups tended to congregate at particular coffee-houses. At Bath, with far fewer such institutions, all parties mingled. The majority of subscribers would be visiting gentry, for the coffee-house offered a temporary headquarters, acceptable company, and certain basic facilities - such as a place to eat breakfast for those staying in lodgings. The Grove Coffee-house, where Charles Morgan succeeded Thomas Sheyler c.1731, enjoyed a virtual 20-year monopoly once Benjoy's, its only rival, had gone, and in 1733 it managed to thwart John Wood's plan to extend the Pump Room on the grounds that this might damage the coffee-house trade. Several hundred subscribed each season, including many notabilities. Viscount Percival, for example, mentions in his diary taking part in various instructive debates on political, religious and literary topics at the Grove in 1730 in the company of the Speaker of the House of Commons, a high court judge (Sir Edmund Probyn), the Dean of Exeter, and others.

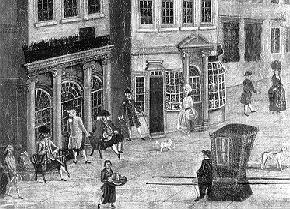

Customers sit outside the coffee-house in Terrace Walk. Detail from a painting c.1780 (private collection).

As the numbers of affluent spa visitors built up and the season steadiliy lengthened, a second coffee-house opened in 1750 close to the old site of Benjoy's, at the busy pedestrian junction of Terrace Walk and North Parade. The building belonged to the silk mercers J & P Ferry, who shared the premises with the coffee-house for another year or two before removing. It may have been then that the billiard room was added and a 'marker' appointed to keep the score, advantages that the Grove Coffee-house apparently never had and which may have cost it custom. A wine-merchant, Richard Stephens, held the Parade Coffee-house 1755-67, followed in fairly quick succession by Robert Boulter, William Mackclary and Peter Temple, before Meshach Pritchard, another local wine merchant, took control 1776-99 - during part of which time he also managed Spring Gardens. At the Grove Coffee-house this long tenure was matched by George Frappell, master 1771-96, who died just as he branched out into a new venture, George's Coffee-house near the Pump Room.

Competition stepped up noticeably in the last third of the century. In the upper town the provision of a coffee room at the new York House hotel in 1769 was followed in 1771 by another at the Upper Assembly Rooms, which was capped within a year by the decision to build on an annexe coffee room beside the front entrance to the Rooms. These amenities serving the population of lower Lansdown were supplemented in 1796 by St James's Coffee-house behind Royal Crescent. In the same way the Argyle coffee-house and tavern (near Pulteney Bridge, from 1790) and the coffee room at Sydney Gardens (by 1798) catered to the needs of developing Bathwick. The fast-expanding local economy of these years also ushered in a subtly different style of coffee-room more geared to business interests and commercial travellers, examples being the rooms opened at the Christopher, Angel and Castle inns (1763, 1782 and 1799 respectively), the Bath Coffee-house in Stall Street (1770-79), City Coffee-house in the Marketplace (1799-1800) and the coffee room for 'respectable tradesmen' at Spring Gardens in 1795.

The Ladies' Coffee-house was far more unusual, a phenomenon possibly unique to Bath, certainly in its longevity. It may have started with a toyshop offering its female customers refreshments and newspapers - sometime before 1740 when the bluestocking Elizabeth Montagu complained of having to hear about everyone's ailments there. By 1755 it seems to have stood on the east side of the Pump Room forecourt, managed by Elizabeth Taylor (of the adjoining jeweller's) and Clementine Ford. In the 1760s and 1770s it was on the opposite side, next-but-one to the Pump Room. Lydia Melford in Smollett's tongue-in-cheek fiction Humphrey Clinker remarks that young women like her were banned from attending because 'the conversation turns upon politics, scandal, philosophy, and other subjects above our capacity.' A lecture on the art of speaking was given there in June 1773 at the time of Richard and Ann Immins' short occupancy, but the room was then let once more and this intriguing institution may not have survived much longer - though a certain Mary Hamilton, lodging in May 1774 in Milsom Street, does record taking breakfast at a coffee-house, perhaps this one.

From Trevor Fawcett, Bath Entertain'd: amusements, recreations and gambling at the 18th-century spa (1998).

See also Coffee-Houses of Old London and Sources for the history of eating-places.