Researching the residences of the higher clergy

A bishop

needs a residence beside his cathedral. From the Norman period this was a

two-storey hall-block, known as his palace, often extended and elaborated in

succeeding centuries.

A bishop

needs a residence beside his cathedral. From the Norman period this was a

two-storey hall-block, known as his palace, often extended and elaborated in

succeeding centuries.

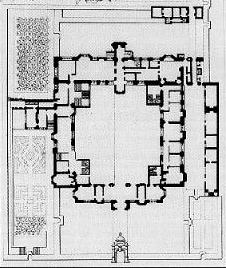

The medieval bishop of an English or Welsh see also needed lodgings in London, since he was often engaged in business there. The bishops sat in Parliament at Westminster. Some held high office. By the 14th century a number of bishops had grand London houses, known as inns.

The Bishop of Winchester was the first provincial bishop to establish a permanent house in London. He owned property in Southwark on the south bank of the Thames and there he built his inn. At the end of the 12th century the Archbishop of Canterbury began Lambeth Palace across the river from Westminster. Other bishops built grand mansions along the Strand, filling the gap between Westminster and the walled city of London. Breaking the trend of building by the Thames, the Bishop of Ely erected his inn on land he had acquired north of Holborn. From the 1530s the bishops' inns on the Strand were acquired by Henry VIII and passed on to the aristocracy. Of all these episcopal town houses, only Lambeth Palace retains its original use.

A bishop owned many manors whose income supported his household. Some were conveniently placed to serve as stopping places between London and his see, or for diocesan visitation, supervision of estates and hunting, so certain manor houses or castles became additional residences, equipped with a chapel, and often more frequently occupied than the palace.

Cathedrals served by a chapter, rather than a monastery, required living quarters for the dean and canons, grouped around the cathedral close. After the Dissolution that applied to all English, Irish and Welsh cathedrals.

Gazetteers and studies

- Thompson, M.W., Medieval Bishops' Houses in England and Wales (1998). Includes sourced gazetteer by diocese, listing the bishop's palace in each case and other properties he used. (Also a study of the type.)

- Schofield, J., Medieval London Houses (1994). Includes bishops' inns.

- Scottish Episcopal Palaces Project (SEPP) was founded in 1995 to investigate the development of bishop's palaces in Scotland up to the disestablishment of the episcopacy at the end of the 17th century.

- The Survey of London includes bishops' inns.

Primary sources

Sources are plentiful for the residences of higher clergy, since documentation for them appears in diocesan records, and those of the dean and chapter, which have a good rate of survival. For the medieval period, chronicles of the see are particularly valuable: most have been published, often by national or local record societies - listed in bibliographies of texts and calendars. As with the laity, medieval bishops subject to the English Crown required a licence to crenellate for fortified buildings. Those issued to bishops of England and Wales are listed by Thompson (see above), appendix 2.

Biographical lists of the bishops, archdeacons and cathedral clergy of England and Wales from 1066 to 1857 can be found in Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae, which has an online index, and subsequently in Crockford's Clerical Directory. Those for Scotland from the Middle Ages to the abolition of Scottish bishoprics are listed in Fasti Ecclesiae Scoticanae.

For additional sources see Researching the history of the Church in the British Isles, images and maps.